When BMW sold venerable British car company Rover in 2000, after six years of ownership, the new management decided to party like it was 1999.

This would be a different kind of car company, they said, one that bunked off motor shows, ran non-PC ads and moved with the kind of creative agility that its German masters had never allowed.

What we didn’t know back in 2000 was the agility with which its bosses – later to be known as the Phoenix Four – set about enriching themselves while attempting to secure the business a viable future. But that’s another story.

Besides the non-appearance at motor shows, the partying also included the more than credible recreations of the Rover 25, 45 and 75 as the sportier MG ZR, ZS and ZT, plus a judicious facelift of the MGF sports car into the (mostly) improved TF. These cars made a promising start, and the ZR even went on to become Britain’s best-selling hot hatchback.

The madness begins

Then came some lunatic, kids-in-a-sweetshop moments, and the quietly growing suspicion that MG Rover’s management wasn’t entirely devoted to issues of business survival. The front-wheel-drive Rover 75/MG ZT would be converted to rear-wheel drive, fitted with a huge 4.6-litre V8 engine from a Ford Mustang and turned into a muscle car. Motorsport specialist Prodrive was commissioned to engineer this complex project, and with decently impressive results given the inconvenient starting point.

However, less than 1,000 MG 260 ZT saloons and ZT-T wagons were sold before MG Rover crashed, speeding the company towards the moment with its sizeable and irrecoverable cash-burn.

There was a Le Mans 24-Hour racing car project, too. True, the famous French circuit was not an inappropriate place for MGs to appear – works MGBs had competed there decades earlier – but funding this escapade when the business had yet to turn a profit seemed like madness. In fact, the MG EX275 Lola showed some promise, mustering a terrific turn of speed if not the necessary reliability. The car would later gain some silverware at other circuits, but not while MG Rover was involved.

Still, at least the top managers enjoyed their track-side 24-hour beer tent.

Creating a halo

But their most eye-brow raising manoeuvre, apart from getting rich, was the decision to buy the failing Italian sportscar maker Qvale. Sorry, who? Qvale Automotive had taken over development of an Italian V8 sports car originally known as the De Tomaso Bigua, which it renamed Mangusta.

But Qvale was struggling, providing MG Rover with the opportunity to buy the project pretty cheaply and develop it into a high performance MG halo model.

The Mangusta had a clever lightweight steel chassis, enabling MG Rover to create an all-new body relatively easily. The task now was to develop that body, which fell to former Lotus and McLaren F1 designer Peter Stevens, now freelancing as MG Rover’s design director. His team’s first shot was the MG X80 (see above), shown as a concept at the 2001 Frankfurt Motor Show and soon considered too tame for the job.

An Italian supercar with added Longbridge

What came next was a machine that Italian chief engineer Giordano Casarini, who came from Qvale with the project, described as a car “that will aggress you”. It wasn’t perfect English, but it captured the SV brilliantly, the MG’s look as unsubtle as a machine gun at a christening.

Squat of stance, bold of nostril, bewinged and big-bonneted, the SV was far from beautiful but it certainly exuded a crude kind of power. Which it almost had: a Ford V8 engine developed by tuning specialists Roush Industries and Sean Hyland throbbing beneath its huge snout, from where it fired 320bhp at the rear wheels.

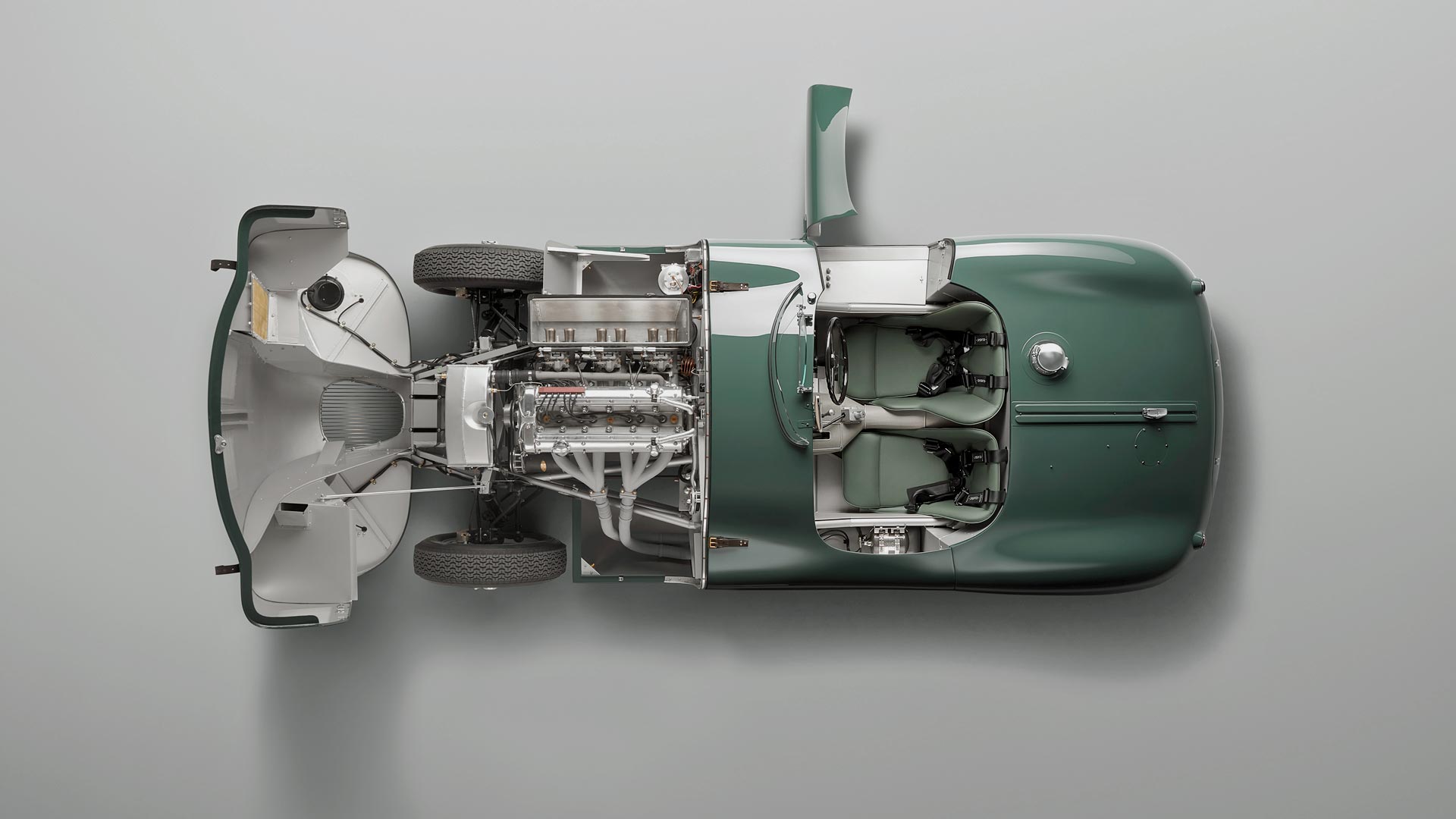

What made this muscle car different was the substance of its body, which was a mix of steel and exotic carbon fibre. The steel chassis was made by Vaccari and Bosi in Modena, the carbonfibre mat was made by Britain’s SP Group and constructed by Italy’s Belco Avia from 3,000 different pieces. The complete shell weighed just 65kg, the 1,495kg SV a spectacular 300kg lighter than the Mangusta.

The chassis and carbon shell were then shipped to Turin’s OPAC Group, a supercar engineering services supplier in Modena whose customers included Ferrari and Lamborghini. They assembled the body around an FIA racing-spec roll cage, before returning it to Vaccari and Bosi for running gear installation.

For a while, MG Rover even had an office in Modena under its MG Sport and Racing subsidiary to mastermind this madly convoluted shuffling of sub-assemblies. But it all sounded quite glamorous, even if the SV’s final trim and assembly took place back in small Kwik-Fit-like workshop in the shadow of the giant factory in Longbridge, Birmingham.

A bargain supercar?

The SV was launched in 2003 as the least expensive carbon fibre-bodied car on sale. Such was the quality of its carbon panelling – which bettered Ferraris of the day – it won MG Rover an award.

But even if you could live with its fearsome looks, the case for the SV was hard to make against the mainstream sports cars you could buy for its absurd £75,000 ticket. Porsche, Jaguar and Maserati all made comparably performing and vastly more desirable machines for less money, and their owners would not need the defence skills of a lawyer to justify their purchase.

SV sales were alarmingly slow, leading MG Rover to develop the more potent 375bhp SV-R. It had a promising 175mph top speed and 4.9 second 0-60mph sprint time – and a still-more-delusional £82,950 price tag. For that, you could have a race-derived Porsche 911 GT3.

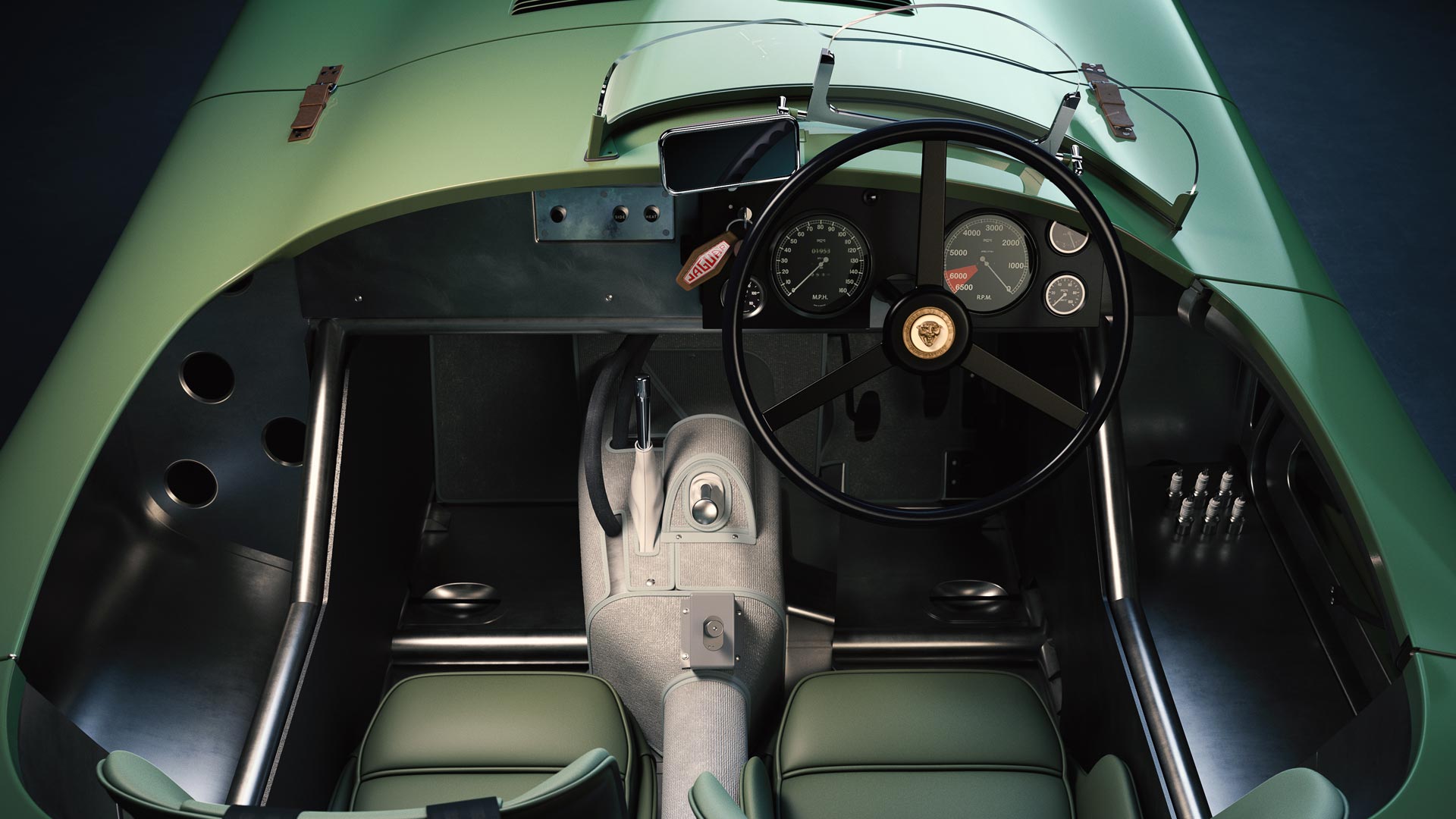

And that was before you unearthed the poor fit and finish of the SV’s interior, the unreachable seat recline knobs, the transmission tunnel-enforced homelessness of your left foot, the map-reading lights that were too dim to read maps by, the cumbersome four-point racing harnesses and the fact that the Ford V8’s power was delivered as if it had woken with a hangover.

Gone and almost forgotten

Plus-points? The MG felt admirably robust, it handled pretty tidily and would cruise a lot more quietly than its vagabond styling suggested. In fact, its manners were almost ludicrously tame for its looks. It was also vastly better than the Qvale Mangusta.

MG Sport and Racing was on the brink of taking a knife to the SV-R’s supercar price tag when its struggles suddenly evaporated. MG Rover plunged into receivership in April 2005 with only 80-odd SVs and SV-Rs produced. The last of these would not find a buyer until 2008.

In truth, MG Sport and Racing was far from unaware of the SV’s shortcomings. It had a made bad car half-decent, and learnt some valuable skills on the way. With these, it was planning a follow-up that would eclipse it with ease. Sadly, that dream was abruptly – and predictably – dashed.

ALSO READ:

Paul Stephens Porsche 993R review