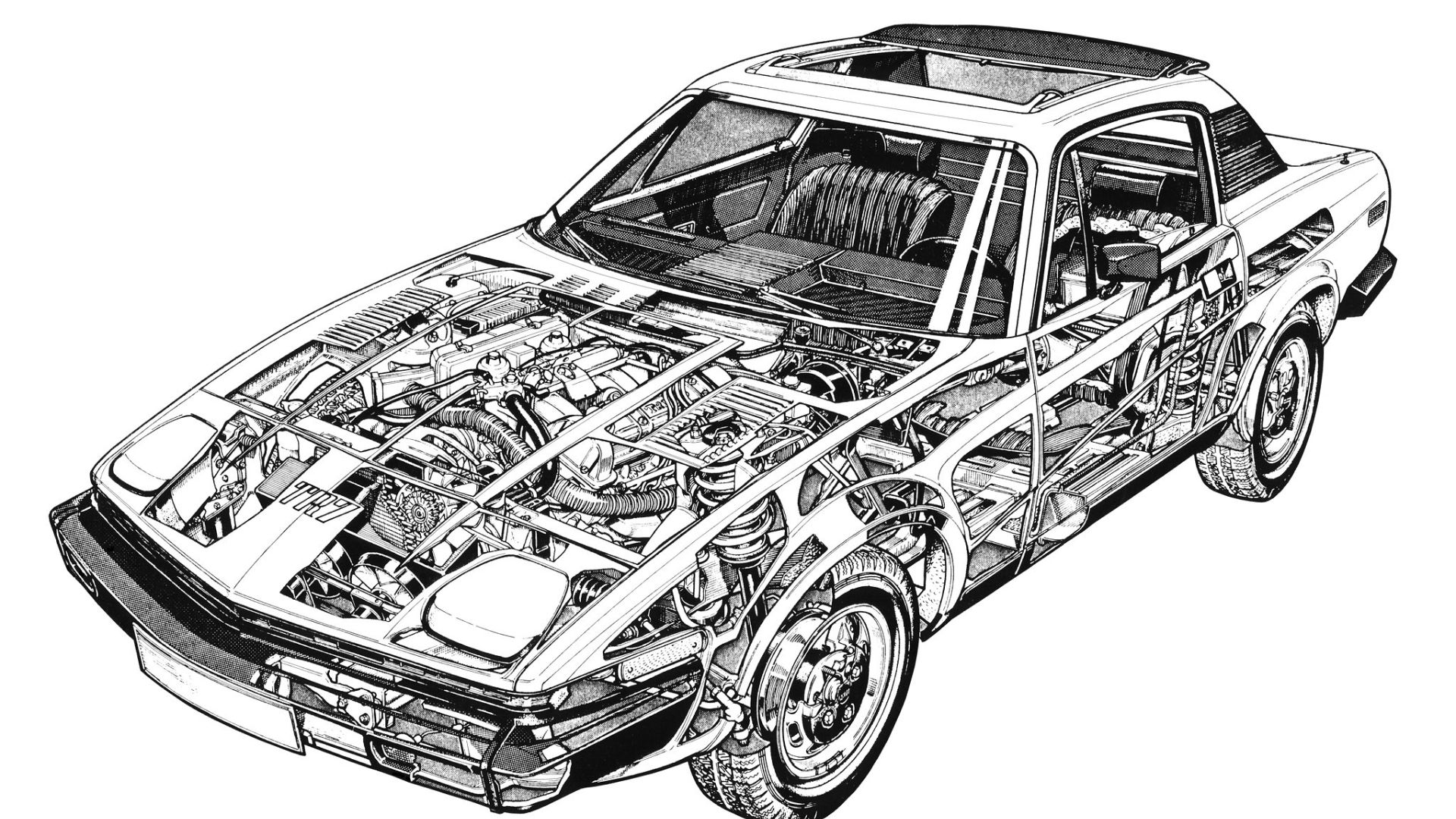

In 1974, Triumph broke with tradition and launched its wedge-shaped TR7 sports car. The advert claimed it was ‘The shape of things to come’. From some angles, it even looked like it.

Nose on from above, for example, when you’d see a sleek, steeply-raked bonnet and pop-up headlights. Or from the side, provided you could only see the front half of the car, its gently flared wings, dipping bonnet-line and neatly integrated black impact bumper – a novelty in the mid 1970s. It promised, well, the shape of things to come.

So, what about the rear half? That was the shocking bit. There was so much to take in, from the abruptly cut roof and its sharply plunging, flat-paned rear window to the clumsily protuberant rear bumper, plus a curious crease line that arced from behind the front wheels to the middle of the rear wing.

Legend has it that designer Giorgetto Giugiaro, then entering the zenith of his career, said “My God! They’ve done the same to the other side as well” when he first saw the TR7 at a motor show.

Today, you can buy a TR7 from around £4,000 – a fraction of the cost of its more traditional predecessors. Perhaps its time as a prized classic will come, but life has never been easy for the TR7…

Startled and confused

The TR7 wasn’t only criticised for its startling styling. British motoring journalists asked why it wasn’t mid-engined like the Fiat X1/9, Porsche 914, Lancia Monte Carlo Spider and any number of supercars – especially when British Leyland was known to have been working on a mid-engined MG sports car.

Instead, this new TR was a front-engined, rear-wheel-drive machine and, more than that, its rear axle was of the cheapskate live variety rather than being independent.

Most controversial of all, though, was the fact that this sports car’s roof was made of steel and firmly welded shut. Weren’t sports cars supposed to be about feeling the summer breeze and seeing the sky above your head?

This, the lack of a six cylinder motor and the TR7’s wedgy contrast to the masculine, brick-like TRs that had gone before all added up to something even more controversial than the equally wedgy Leyland 18-22 Series (soon to become the Princess) revealed at much the same time. Or indeed the Austin Allegro that had lurched onto our roads two years earlier.

A speeding Bullet

However, quite a bit of thought had gone into the Bullet project, as the TR7 was codenamed. Two top British Leyland engineers had travelled to the United States – by far the biggest market for Triumph and MG sports cars – to sound out a range of experts on how the Triumph TR6 should be replaced.

Almost all of them said mechanical simplicity was essential. They didn’t want the independent rear suspension of the TR6, they wanted a simple four-cylinder engine and they certainly didn’t want an exotic and difficult-to-repair mid-engined layout.

So the Bullet got all of these things, plus a fixed roof, because it looked like the US government was going to legislate convertibles out of existence for safety reasons. And while it had that live axle, it was well-located with four links. This and long-suspension travel provided the car with ride and handling far more sophisticated than any previous TR had managed.

A badge-engineered MG?

However, Bullet wasn’t necessarily going to be an adventurous wedge-shaped car at this point. British Leyland’s management and boss Sir Donald Stokes had yet to decide on design proposals coming from Triumph and the Austin Morris design department.

Austin Morris was involved because BL also had the problem of replacing the MGB, although the sports car and its GT coupe stablemate were still setting sales records in the US.

With BL as cash-poor as a gambling addict, there were thoughts of badging Bullet either as an MG, a Triumph, or with minor modifications (that would probably be badges, then) both.

A new TR was the priority, though, and Triumph put forward a model based on earlier work by Italian designer Giovanni Michelotti, who had produced several very successful models for the company – the Herald, Spitfire, GT6 and TR4 among them.

A clean-sheet design

Austin Morris design boss Harris Mann, on the other hand, had a clean sheet of paper and set about creating a more dramatic sports car with American tastes in mind. The decidedly rakish angle of his car’s windscreen was designed to allow the driver to see America’s overhanging traffic lights, for example.

The result was as arresting as a giraffe in a shopping mall. Mann’s startling slice of wedge was worthy of a blister-packed ‘Hot Wheels’ toy.

And it was Mann’s design that won the styling model face-off, with only a handful of management attendees voting for the more old-fashioned Triumph proposal. Triumph’s engineering team did at least get the job of developing the car, and providing the so-called ‘slant four’ engine that enabled Mann’s steeply-sloped bonnet to enter production.

What didn’t make it were Mann’s hidden door handles and his neat flip-up headlamp covers, the engineering department forcing a shape that was distressingly close to a pair of toilet lids. At least they were body coloured… until the paint began to peel off their top surfaces.

Not that this was the most serious of the early TR7’s deficiencies. “Unfortunately the (styling) buck was the only TR7 where the panels fitted and the wheels filled the wheelarches,” reckoned one of BL’s senior US managers. And he was not wrong.

The Speke factor

The TR7 was to be produced at BL’s Speke plant in Liverpool, a factory notorious for an unruly, strike-prone workforce. They transferred to the assembly line many of the skills they’d learned from the docks they were recruited from. Among these were gold-standard pilfering, and a lack of cooperation as shocking as the TR7’s styling.

There were workers who wanted to work, but their efforts were undermined by the political militants, whose rebelliousness was fired by the presence of the Workers Revolutionary Party and the International Socialists, few of whom actually worked at the plant.

All of which meant that the TR7 was shoddily built and often not built at all, so frequent were the strikes. Not all the faults were introduced by factory staff, however. Inaccurate body tooling ensured that the doors were too big for their apertures, for instance.

Rain often prompted one or both of the car’s headlights to go on strike, like their assemblers, and on some cars an emergency stop would have the windscreen popping out, as its advanced, heat-bonded seal failed to stick.

Success against the odds

Despite all this, dogged work by BL’s American team (who cobbled together a barely acceptable bunch of press demonstrators by cannibalising some cars) meant the TR7’s American launch in 1975 was a success.

Poor brakes and a vibratory engine were criticised, and many found its styling less than beautiful, but they welcomed a car that looked refreshingly radical and loved the comfort of its exceptionally well-designed interior.

It was also quite keenly priced, it rode and handled well, delivered adequate performance and was far more civilised than any British sports car that had come before. And Americans were already migrating to coupes from convertibles, encouraged by the arrival of the desirable Datsun 240Z.

Europe did not see the TR7 until 1976, the priority being the US market. And just two years later the car’s career looked like it might be all over, thanks to a five-week strike that began on the day BL’s new South African boss Michael Edwardes arrived, tasked with sorting the government-owned British Leyland out.

Some of this early sorting meant shutting the section of Speke factory that made the TR7. However, despite the fact that the car itself had made no money – and that even Prime Minister Jim Callaghan, to whom Edwardes was ultimately answerable, reckoned it should be killed off – the car was transferred to Triumph’s Coventry plant.

The TR7 survives

More than 200 improvements were made in the process, most of them aimed at fixing poor quality – although the doors still didn’t quite fit – and the TR7 briefly entered a more stable period.

Highlights were the arrival of a convertible, which rid it of the turret-top roof that many hated, and for the US, the impressive V8-powered TR8. Convertible-killing legislation never came to America, and the drop-top TR7 turned out to be a pretty agreeable machine.

More upheaval was to come – literally – with the closure of Triumph’s Canley plant, which saw TR7 production moved once again, this time to Rover’s Solihull factory. With the move came another mild quality upgrade, and plans to introduce the TR8 in Europe.

Unfortunately, by now the TR7’s sales trajectory was much the same as the sinking crease lines on its flanks, and it would not be long before its viability was called into question.

That saw the European TR8 programme cancelled, and by 1981 the plug was pulled on the whole project – despite several attempts, one of them a risible MG rebranding, to save the car.

The end of the TR7 – and Triumph

Born nearly 50 years ago, the last TR7 was built on October 5 1981, ending the long and (mostly) successful career of TR sports cars – and, in truth, of Triumph as well. The Acclaim saloon, launched at much the same moment, was little more than a rebadged Honda.

With a tumultuous history like that, and styling that still startles for many of the wrong reasons, it’s easy to view the TR7 as a total failure. In profit terms it almost certainly was, but the car turned out to be the most produced of all the TRs, scoring 112,368 sales during its six turbulent years.

Had it been better made, that number could easily have been higher, enabling the fulfilment of a development programme that also included the Lynx 2+2 coupe and a 16-valve model.

Like so many British Leyland stories, though, this is another one peppered with wistful ‘what-ifs’.

ALSO READ:

1972 Jensen Interceptor review: Retro Road Test