Think of revolutionary, post-WW2 cars from Britain, and one small thought immediately comes to mind: the 1959 Mini. Twelve years before this country’s most famous car was launched, however, there was another quietly brilliant, rule-bending machine.

Like the Mini, that car would win silverware in the Monte Carlo rally. It would also demonstrate that fast cornering in a family car needn’t be a torrid affair. It was even the first British car to have a curved windscreen. Like the Mini, its design was largely the work of one man.

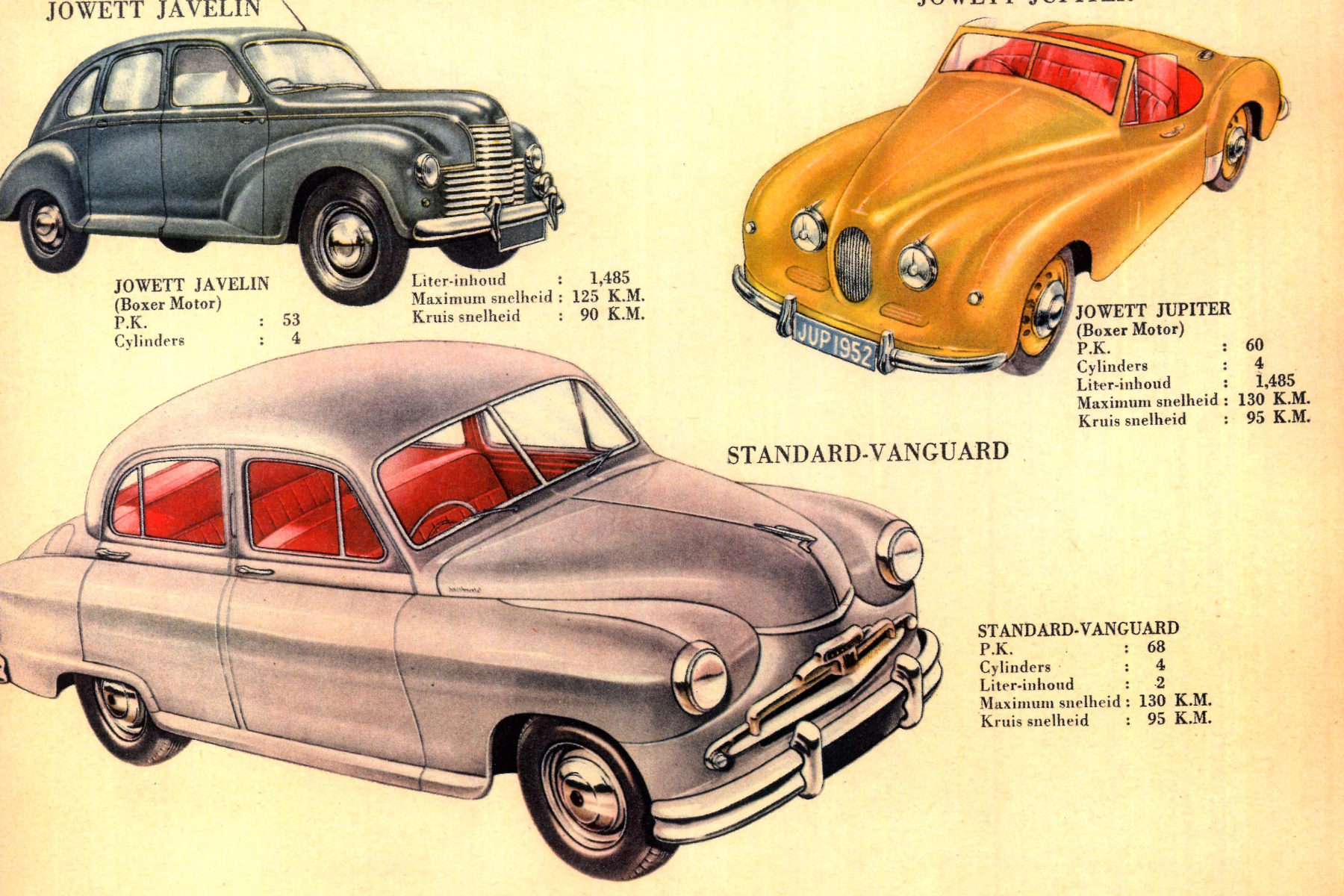

That car was the 1947 Javelin. Compared to most of the warmed-over, upright, separately mudguarded pre-war throwbacks that most British carmakers were building in the late 1940s, the Javelin was a peek into a brighter future. Its origin was as surprising as its streamlined silhouette, hailing from the Yorkshire-based Jowett company.

Born in Bradford

This was relatively small outfit compared to the dominant Austin, Morris, Hillman, Ford and Vauxhall of the day. Its pre-Javelin range mostly centred around a tough 1.0-litre twin-cylinder engine that the founding Jowett brothers had developed in 1910. This motor was usually found propelling vans and utilitarian family cars, which would have complemented homes with no bath and an outside toilet.

The vehicle Jowett was most dependent on for its business was the Bradford van, a 1946 rework of a 1932 design that nevertheless found 38,000 buyers. Many of them were overseas and, presumably, given its 55mph top speed, most of them had time on their hands. The Javelin, however, was capable of a far headier 80mph: eye-widening pace for a late-1940s family car. And it had the looks to go with it.

Still, what made the Javelin especially special was more than its clean, fastback shape. Its creators were well ahead of their time for conceiving it as a world car: suitable not only for the UK, but also Europe, North America and Africa. Designer Gerald Palmer was better qualified than many for the task, having grown up in southern Africa. His dirt road experience determined several Javelin fundamentals, among them eight inches of ground clearance and the unusually strong chassis that was partly responsible for its fine handling.

Slippery as a fish

Like Mini designer Alec Issigonis, Palmer was a lot more than a stylist, his considerable engineering skills enabling him to design the entire car, engine included. Apart from aiming for the robust, he also wanted a sleek body with plenty of passenger space. The Jowett’s aerodynamic properties were part-guesswork, the car never seeing the inside of a wind tunnel, but there was a widely held view at the time that, ultimately, cars would resemble the teardrop shape of a fish.

In many ways that was right, Palmer’s attempts leading to a sloping tail, fared-in rear wheels and the absence of running boards. The curved windscreen would have helped as well, glass maker Triplex offering Jowett the chance to be first in the UK with this feature.

The roomy cabin – a front bench seat allowed room for six – was achieved by mounting the Javelin’s 1.5-litre engine well forward. It was a bit more compact than a conventional in-line four-cylinder engine because of its Subaru-style ‘boxer’ layout, yielding a shorter block.

Race and rally success

Flat-fours were not new to Jowett. The company had sold some before WW2, the layout being a logical development of the company’s flat-twin. But this engine was all-new, and the work of Palmer.

He also designed the car’s space-efficient, all-independent torsion bar suspension (most other rear-wheel-drive cars still had a live axle suspended by cart springs). The result was a ride that kept a Javelin man’s tobacco in his pipe, and roadholding grippy enough to get auntie Gertie all in a fluster.

All of this contributed to the car’s slightly unexpected class win in the 1949 Monte Carlo rally, in which Palmer was a co-driver. This success was followed by a still more impressive class win in the Spa 24 Hours, the Javelin soon gaining a name as a car for the sporting chap.

They think it’s all over

It also gained plenty of press accolades, with The Motor concluding the Javelin had ‘a combination of qualities rendering the car unrivalled in its field’. Jowett’s gamble on a new car, a new engine and advanced new factory equipment to build it looked like it was paying off. And having finished this design, Palmer was head-hunted by the Nuffield Organisation to design new models for Morris, Wolseley, Riley and MG.

Sadly, he left behind a company whose success would turn to failure. In an effort to save money, Jowett designed its own transmission to replace the bought-in unit, but the ‘box was not up to the job. Of the first 1,000 cars fitted with it, 78 suffered failures, with early cars also prone to overheating and fracturing crankshafts.

Jowett ultimately upgraded the engine into quite a tough performer, but by then the Javelin’s poor reputation, and a shrinking UK market, saw the sales graph plunge.

The Javelin’s body supplier had also been bought by Ford, which continued to honour the contract to the point that Jowett ended up having to store bodies around Bradford, the football ground included, because sales were so slow. Body supply was temporarily halted in 1952 and was never restarted, as Jowett ceased trading in 1954.

A Great Motoring Disaster

The company had over-reached itself, introducing too many new components and systems, then failing to test them adequately. Had the Javelin been more reliable, it could have propelled Jowett to new heights. As it was, only 22,700 were built – less than the geriatric Bradford van.

The British car industry has many stories of brave failure, just as American, German, French, Italian and Japanese car manufacturers do.

What made the Javelin different, though, apart from its striking looks, was the quality of thinking that went into its design. It’s a real shame the same effort wasn’t invested in making it reliable.

ALSO READ:

1972 Jensen Interceptor review: Retro Road Test

Although the rest of your comments are very interesting, I must take issue with your assumption that “The British motor industry is littered with failures”, (or words to that effect),. WHAT failures? In the past, manufacturers didn,’t test new models thoroughly enough before releasing them, thus gaining a reputation for unreliability, which stuck, and affected sales. Not just Jowett! By co-incidence, this was also the case with the Stag, which sold the same amount as the Javelin!

El Jowett Javelin fue una adelanto para su época.

Poseo uno y aún funciona. Y vivo en Uruguay.

Saludos